Republished by Ken Trotman Limited 2022

Charles Kinloch

On 5 January 1806 Charles Kinloch was commissioned as an ensign in His Majesty’s 52nd (Oxfordshire Light Infantry) Regiment of Foot who were then based at Shorncliffe barracks, made famous by the innovative light infantry training carried out there by General Sir John Moore and he rose to the rank of lieutenant in 1808.

He was not to remain here long before active service called; he served at Copenhagen before proceeding to Portugal to take part in Wellington’s first Peninsular campaign. Returning home, he sailed with the ‘Great Expedition’ to Walcheren in 1809 and then returned to Spain for the campaigns of 1810-12; when his foreign service was rudely halted by a severe wound received in the carnage of the breach at the final assault on the fortress of Badajoz. Captain John Bell, a fellow participant in the storming wrote to Charles mother shortly after ‘Milton himself would have been ashamed of his description of hell, if he could have seen the storming of the breaches, and the only thing that astonishes us, is, not that we did not get in, but that any one was got away.’

Forced to return home to recuperate, Charles worked tirelessly to gain his captaincy and a Staff appointment. Indeed much of his correspondence at this period is particularly fascinating in revealing the intricate machinations required to make oneself a prime candidate for such posts in the British army of the Napoleonic wars. Party, power and influence helped build tortuous chains, all of which backed by copious amounts of hard cash, had much to do with the rise of many young officers, not least the Duke of Wellington himself. Charles Kinloch was not above such scheming and these trials and tribulations, false dawns and shattered hopes, form an integral part of his story and provide much of interest regarding the ‘Purchase’ and ‘Staff’ systems which held sway at this period.

Eventually the scheming paid off, he became a captain by purchase in the 99th Foot in March 1813, transferring back to the 52nd in the following July. More importantly, Charles also succeeded in gaining a Staff appointment, having been appointed as an extra Aid de Camp to General Sir John Hope, later created Lord Niddery before inheriting the Earldom of Hopetoun, in January 1813. Hope commanded the 1st Division of Wellington’s army throughout the campaigns of 1813 and 1814 and was second in command to the Duke.

Charles joined him in France and was to be heavily involved in overseeing the construction of that engineering masterpiece, the bridge of boats over the Adour and the subsequent blockade of Bayonne. Indeed he was to become a unique eye-witness to the wounding and capture of Sir John Hope during the infamous sortie from Bayonne, that unfortunate last gasp of the entire campaign. His letters of this period are of particular value and bring new light upon aspects of this final campaign in Southern France.

With universal peace proclaimed, Charles was to return to his regimental depot and was unfortunately not fated to join the 1st battalion in Belgium until after that ever memorable day at Waterloo, where Colonel Colborne marched his regiment onto the flank of the Imperial Guard and into immortality.

Joining the regiment in Paris, Charles toured the French capital; avidly visiting the accumulated treasures of Europe then housed in the Louvre and was a witness to their forced repatriation by allied troops.

Finally, Charles was to become just one more casualty of the peace dividend as the government rapidly de-mobilised thousands of soldiers and sailors, going on half-pay in July 1816 and thus ending his military career.

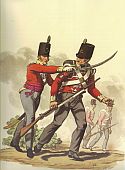

An Officer and Private of 52nd Foot

Reviews

…it is well worth the money. Gareth Glover has once again done his normal superb job of editing.

Robert Burnham, Napoleon Series