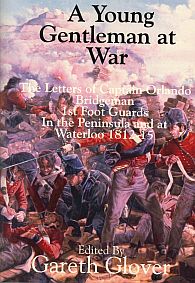

A Young Gentleman at War

The Letters of Captain Orlando Bridgeman, 1st Foot Guards, in the Peninsula and at Waterloo 1812-15

Recently republished in Napoleonic Archive Volume 11

A few years ago I obtained copies of the letters of Captain Orlando Henry Bridgeman from Staffordshire Record Office, since when these copies have lain half forgotten and gathering dust in my to do pile on the book shelves of my study. Having eventually turned my attention to this mound of papers and began the work of transcribing them, I soon realised what a wonderful collection of letters they were; Orlando wrote with a real freshness, adding a few more paragraphs each day as things occurred, until the day the letter must be sealed for the packet to England. Everything was new and exciting to him and he took great delight in describing the wild scenes that unfolded as well as explaining the humdrum of army routine to his parents and siblings, who were ever hungry to hear of his adventures in Spain and Portugal. This immediacy and attention to the details of army life make these letters of inestimable value to military historians without detracting from the enjoyment of the more general reader and I do hope you enjoy reading this book as much as I enjoyed compiling it.

Orlando Henry Bridgeman was born on 6th May 1794, the third son of Orlando Bridgeman, the 1st Earl of Bradford and Lucy Elizabeth Byng of that both famous and notorious seafaring family. Orlando’s eldest brother George Augustus Bridgeman was to be groomed to inherit the family estate of Weston in Staffordshire; his younger siblings were then to be divided amongst the time honoured professions traditionally open to the landed gentry in Georgian times. Their second son Charles went to the Navy, Orlando the Army and his younger brother Henry the Church; Lucy the youngest sibling of the five and the only girl was not to be worried by such matters.

Orlando was commissioned as an ensign in the 1st Foot Guards in 1811 and joined his regiment in London. In early 1812 the regiment was ordered to Spain and Orlando was to spend the next year with his battalion suffering under the broiling sun at Cadiz, the Spanish city being under siege by a French army under Marshal Soult. His letters of this period are very informative regarding life in the city under regular bombardment and the very basic conditions suffered by the troops, both men and officers, in the defensive lines manned by the British and Spanish troops. Orlando, like many of his counterparts, did not form a particularly good impression of the Spanish people or their commitment to the war effort at Cadiz, but he did reconsider these views later, having seen many other parts of Spain and eventually looked upon them in a more favourable light.

The siege eventually being lifted, his battalion marched across Spain to join Wellington’s army at Madrid; a long trek which Orlando missed through ill health and thus luckily also missed the dreadful retreat back into Portugal that autumn. Having rejoined the battalion in Portugal, Orlando was again frustrated in his attempts to experience a great battle; the 1st Guards being forced to recuperate at Oporto because of the large numbers of sick in the hospitals and therefore missing the glorious victory at Vitoria.

Orlando was finally given his baptism of fire in the hellish scenes of the assault on the fortress of San Sebastian where he formed one of the `volunteers’ sent by Wellington to show the 5th Division how to assault a fortress, following the disastrous failure a few weeks earlier. Orlando was to see good friends die that day and was wounded himself, causing him to miss some of the early fighting of the invasion of France, but he does provide much important information regarding his battalion’s role in these actions, as his knowledge undoubtedly came first hand from his friends still with the battalion.

With promotion to Lieutenant & Captain Orlando returned to London to the 2nd Battalion; he remained there when most of the battalion was sent to Holland in 1814 and eventually transferred to the 1st Battalion; but the peace of Europe was soon shattered by the return of Napoleon to his throne. Orlando went to Belgium as an Aide de Camp to Sir Rowland Hill who commanded the 1st Corps, one of Wellington’s most reliable commanders in Spain. Orlando was employed throughout the battle relaying orders and was again wounded but not seriously, towards the end of the battle and rejoined the army before Paris fell to the allies; his letters regarding this fascinating series of events are therefore of great interest.

Following their return to London the following year, Orlando seems to have lost interest in the army, with little prospect of advancement in a much reduced peacetime complement and becoming financially secure having married his life long friend Lady Selina Needham on 5th July 1817, daughter of 1st Earl of Kilmorey, he retired on half pay in 1819. He had four children by this marriage, Francis Orlando Henry born in 1819; Orlando George 1820; Orlando Jack Charles 1823 and Selina 1825 before his premature death at the age of just 33 years at Hastings on 28th August 1827 and was buried at Teddington church which was one of his brother Henry’s livings.

There are few first hand accounts published from the 3rd Battalion 1st Guards at this period. Ensign Howell Rees Gronow did serve in the battalion for the last few months of the war in Southern France as did Ensign Robert Batty and both their accounts and a number of other officers who replied to William Siborne’s appeals for information are available regarding the Waterloo campaign. I have however not found any other first hand account of the battalion’s important services at Cadiz and at the siege of San Sebastian. For this reason alone Orlando Bridgeman’s letters are an important new source for students of the Peninsular war.

Whilst researching these letters one important story relating to Orlando has been found to be untrue.

The life of an officer of the Guards has never been and probably never will be the same as that of the basic infantry officer. The pedigree of the families of these officers, their personal fortunes and their family connections with many of the more senior officers of the army ensured that their lives were appreciably more comfortable, not just on home service but also on campaign. It is frankly astounding to see how many of the officers nominally of the Guards were actually absent on duty as staff officers at any one time. Orlando was no different, he may not have had a over generous allowance from his father but his family connections certainly opened many doors for this young man, indeed he appears to have spent much of his campaigning, living with some senior officer or other and dining at their table. Their social life was hectic, for everyone wanted these eligible young dandies at their functions and the merchants happily procured the finest luxuries for their table or billet. Their world was one of privilege and luxury but when asked to fight, these same young gentlemen fought like lions. Through the eyes of Orlando Bridgeman we now can take a unique peek into their world.

Reviews

A Young Gentleman at War is among my favourites. It is well worth the money!

Robert Burnham, Napoleon Series